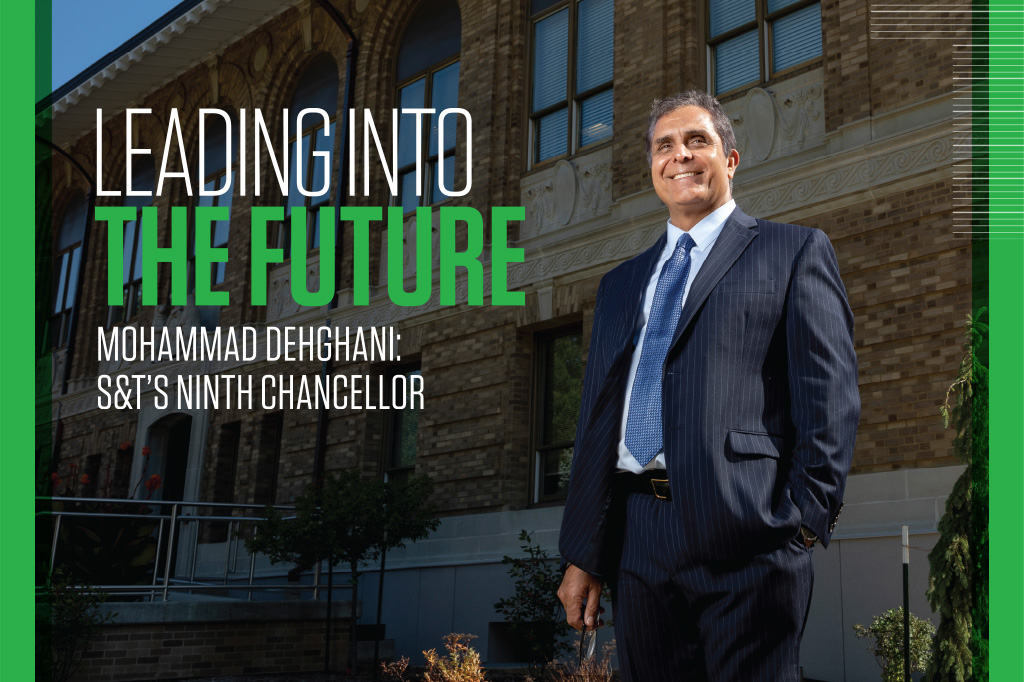

Leading into the future

Posted by Lindsay Stanford

Mohammad Dehghani: S&T’s ninth chancellor

Mohammad Dehghani was perplexed.

A project engineer at California’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), he was assigned to work on a fusion reactor. One of the tasks of that complex project involved insulating a large stainless-steel chamber from the “thousands and thousands of volts of electricity” that would flow through it.

“We needed a massive ceramic ring to insulate the chamber and attach it to the rest of the system,” Dehghani says.

Finding a material that would withstand the metal expansion that occurs at 800 degrees Centigrade was a challenge. Under such intense heat, the steel would expand more than the ceramic ring, causing the vacuum seal to fail.

So Dehghani consulted with experts, hoping to find the answer to this technical dilemma. He talked to others at Livermore, a $1.8 billion, 7,000-employee national lab known for solving all kinds of complex engineering problems. He contacted material engineers at universities in the California Bay area. No one seemed to have an answer.

Finally, someone suggested he contact Missouri S&T’s ceramic engineering department.

“We found a faculty member at Rolla” — Dehghani doesn’t recall the name — “and during the very first conversation, he offered the simplest, most awesome solution.

“I vividly remember him saying, in our phone conversation, ‘Why don’t you assemble the system at mid-temperature range’?” That is, assemble the apparatus at 400 to 500 degrees, so that the ceramic ring will only experience the ramp-up and ramp-down within the tolerable degree range.

In retrospect, Dehghani calls the solution “a no-brainer” and wonders why he hadn’t thought of it himself. But it also stumped other great minds at Livermore, Stanford and Berkeley, so he was not alone.

“We all were focused on either finding a novel material with expansion properties similar to those of steel or on redesigning the entire system,” he says. “We were too close to the system and too much in the soup.”

The Rolla faculty member’s creative yet pragmatic approach to solving this technical problem typifies the character of Missouri S&T in Dehghani’s mind. He calls it “solution-oriented research along with cutting-edge education to prepare S&T graduates who are career-ready engineers and scientists.” It’s one reason he was drawn to the chancellor’s role here.

“Missouri S&T has always been a nationally recognized school focused on engineering and the sciences,” Dehghani says. “In my mind, I always equated it to Michigan-Ann Arbor or Wisconsin-Madison. So, when I received the call to let me know that I was nominated for the position of chancellor, I was over the moon.”

A strong R&D background

On Aug. 1, Dehghani became the 22nd leader in S&T’s 149-year history and the ninth to hold the title of chancellor. He comes with a strong background in research and development — the kind of applied research that S&T is known for.

A native of Tehran, Iran, he joins Missouri S&T from Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, where he served as vice provost for research, innovation and entrepreneurship for six years. Dehghani succeeds Christopher G. Maples, who served as interim chancellor from May 2017 through July 31, 2019.

Dehghani earned three degrees in mechanical engineering from Louisiana State University then went to Massachusetts Institute of Technology on a postdoctoral fellowship from the National Science Foundation and the American Society of Engineering Education.

“Several of my high school friends in Tehran were Americans whose families lived in Iran for various work reasons or were children of mixed American-Iranian parents,” he says. “Naturally, I was curious to see the places that my friends had come from and so I decided to pursue my college education in the U.S.”

Over the past 22 years, Dehghani has taken on leadership responsibilities at two major research universities and two national laboratories, Livermore and the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). Prior to joining Stevens, Dehghani was associate director for engineering, design and fabrication at APL and a member of the Johns Hopkins mechanical engineering faculty. He also served as founding director of the Johns Hopkins University Systems Institute (JHUSI), where he worked with the Department of Defense, the National Institutes of Health and other federal agencies.

Before joining Hopkins in 2008, Dehghani was at LLNL, most recently as the division leader of the research lab’s New Technologies Engineering Division. He oversaw a staff of 450 involved in a wide array of disciplines, from biomedical and environmental engineering to mechanical, structural, nuclear and computational engineering to process systems.

He also spent a dozen years as a tenured faculty member in mechanical engineering at Ohio University and worked in private industry in Baton Rouge while pursuing his Ph.D.

Focusing on the new “3 R’s”

Since joining S&T, Dehghani has set about learning as much as he can about the campus and the UM System. That’s no surprise, given his approach to solving problems and his reputation as a team-builder and collaborator.

Dehghani sees Missouri S&T as an “ecosystem” in which success can thrive on many levels.

Chancellor Dehghani hosts a meal for members of the Chancellor’s Leadership Academy, a program that helps second-semester freshmen develop effective leadership skills.

Dehghani and other campus administrators served frozen treats and fist bumps to faculty, staff and students at S&T’s annual ice cream social.

“The essential elements of an excellent university are excellent students and excellent faculty and staff,” he says. “A well-balanced academic ecosystem, where faculty and students are excited about their steady progress in research and academic endeavors, will become a destination of choice for the types of faculty, staff and students that will help us achieve our horizon goals. … We need to focus all our efforts to create and maintain a thriving academic ecosystem and enhance S&T’s well-deserved national and global standing of relevance and importance.”

He plans to home in on growing the “3 R’s” of recruitment, retention and research.

“It’s important that we grow in all three areas,” Dehghani says. “If we only recruit students but don’t retain them, then we do a disservice to those students and to society. If we strengthen our research efforts, we will be able to recruit more graduate students as well as raise our profile nationally and internationally.”

He’s quick to add a fourth R to his list: reputation.

“With the right recruitment, retention and research strategies in place, we will be well-positioned to take S&T to a higher level of national recognition and relevance,” Dehghani says. “To do that, we must also create new, modern programs in many areas for students who are interested in being a part of the solution to grand global challenges.”

Equipping ‘worldly engineers and scientists’

It’s an ideal time to start new programs that build on S&T’s traditional STEM strengths by connecting with the university’s exceptional humanities and liberal arts programs. Already, Dehghani is pushing for a new international engineering program that will combine engineering disciplines with languages such as French, German and Spanish, and he has asked a non‑engineer, Audra Merfeld-Langston, chair of arts, languages and philosophy, to lead its development.

That’s the type of non-traditional approach you can expect from Dehghani. His background of addressing problems in complex systems — as he has done throughout his academic career — will come in handy at S&T.

S&T’s job is to equip “worldly engineers and scientists to articulate their approach to solving the ever-more-complicated global challenges and convince social, political and economic leaders of the urgency of such solutions,” Dehghani says. These include headline-grabbing subjects like climate change, renewable energy and food security as well as medical and educational challenges and the ever-expanding supply chain, logistics and transportation needs of a global economy.

“If they are equipped with a good level of awareness and understanding of history, philosophy, social sciences and liberal arts, our graduates will gain significant traction in selling their ideas and will be able to provide critical contributions to these global challenges.”

A historical context

Dehghani has equipped himself with an understanding of these disciplines. In addition to enjoying the Persian poetry and history of his native Iran, he reads broadly about a range of historical topics, but three in particular: the history of technology and science, medieval history — “the incredible drama of wars and belief systems of the middle ages fascinates me,” he says — and the American Civil War.

“I consider the opportunity to serve Missouri S&T as its chancellor a personal and professional honor as I recognize the recent and historic achievements of this great institution.”

Among his favorite reads: The Discoverers, by the late Daniel Boorstin; Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror, March of Folly and The Bible and the Sword (“great oldies,” he calls them), and the writings of Henry Petroski, a civil engineer and historian at Duke University. “And any book on the Civil War will make you wonder about this perversion of logic called war,” he says.

Reading history is more than a great pastime for Dehghani. He also studies history because — and here he draws from another liberal arts discipline by paraphrasing philosopher George Santayana — “I do not want to be doomed to repeat it.”

A fitting perspective for a chancellor who joins Missouri S&T at a significant moment in its history. The campus will soon commemorate its 150th anniversary, and Dehghani — history buff that he is — is learning as much as he can about the university’s past as he leads S&T into the future.

“I consider the opportunity to serve Missouri S&T as its chancellor a personal and professional honor as I recognize the recent and historic achievements of this great institution,” Dehghani says. “Missouri S&T is at an exciting point in its evolution to enhance its national standing and achieve further prominence among top public, land-grant research universities.”

About Mo Dehghani

- Born 1955 in Tehran, Iran

- Married to Dr. Mina (Saffari) Dehghani, a pharmacist and pharmacologist

- One son, Devon, age 13

- One dog (a Brittany spaniel named Ginger) and Two cats (an orange and white tabby named Masghati after the chancellor’s favorite childhood dessert, and Asal, which means honey.)

- Education: Louisiana State University, mechanical engineering (B.S. 1980, M.S. 1982, Ph.D. 1987)

- Postdoctoral experience: Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1988)

- Career experience: Ohio University (1987–1996); Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (1996–2008); Johns Hopkins University (2008–2013); Stevens Institute of Technology (2013–2019)

- Professional affiliations: International Council on Systems Engineering; American Society of Mechanical Engineering; American Society for Engineering Education; Project Management Institute

- Hobbies: Flying (licensed pilot), fly fishing, reading