Honglan Shi: water woman

Posted by magazine

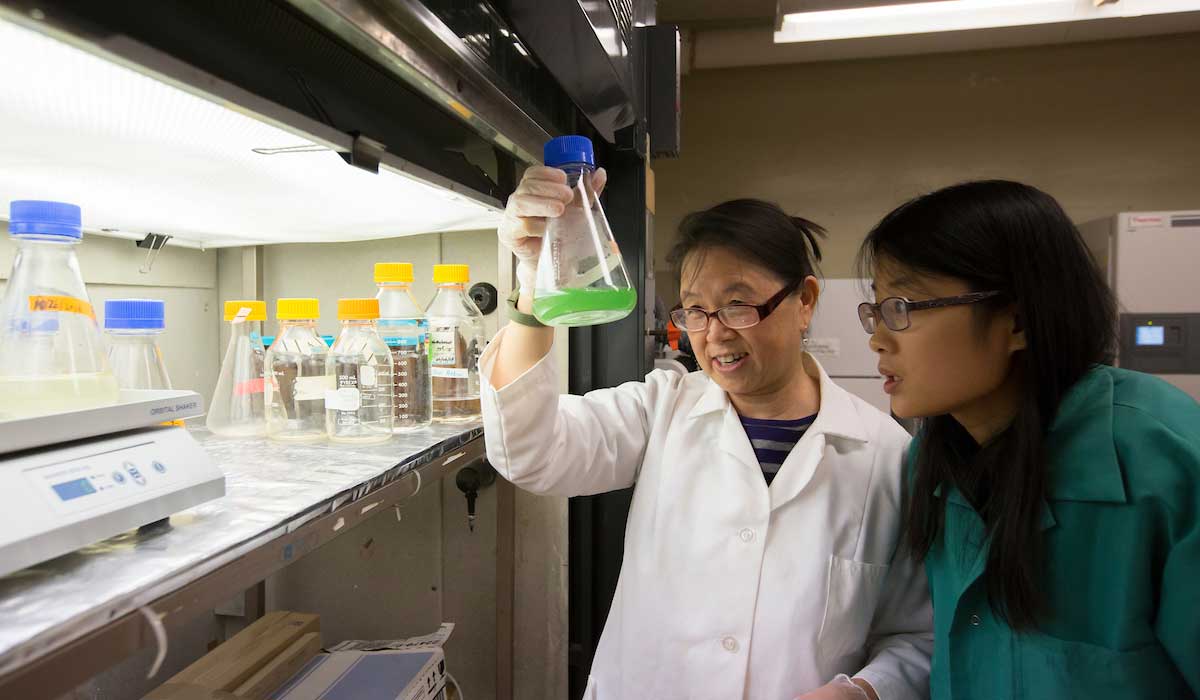

In her Schrenk Hall laboratory, Honglan Shi and her students conduct water quality research. They grow tomato plants in different types of water, and use potassium permanganate (in the purple vial top right) to treat Microcystis, a freshwater cyanobacteria often called “blue-green” algae (top left). Potassium permanganate is used extensively to treat drinking water.

Honglan Shi has gained a national reputation as the go-to drinking water quality expert.

Shi, a research professor in chemistry at Missouri S&T, and her team are testing water to find and correct taste and odor problems and to screen for algal toxins and other harmful compounds.

Water treatment plants often use large amounts of activated carbon to control taste and odor, and that gets expensive. Shi’s team is trying to determine the most effective active carbons to use, while also removing harmful pesticides and herbicides.

Shi says the research is important because the Missouri River provides drinking water to more than 60 percent of Missourians, and the river water frequently has taste and odor problems.

“Treatment plants along the Missouri River have to use large amounts of activated carbon to control taste and odor,” Shi says.

The more carbon used to treat the water, the more money spent by the utility. These costs are often passed on to the customers.

While drinking water taste and odor problems might cause consumers a bit of apprehension (or make them hold their noses), Shi says a greater threat looms.

“The worry right now from the whole world is that algal blooms are becoming more and more serious,” Shi says. Certain algae are associated with illness and environmental issues.

“Everywhere, people are trying to figure out what to do if a harmful algal bloom happens. Because whenever they bloom, they spread very quickly and no one can drink the water.”

Toxic algae blooms are especially prevalent in hot seasons and eutrophicated water. Eutrophicated water lacks oxygen, and eutrophication is caused by the addition of excess nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphate into an aquatic system.

The most frequently reported type of toxic algae is Microcystis, a freshwater cyanobacteria often called “blue-green” algae. Ingestion or inhalation of Microcystis may, within several hours after exposure, lead to abdominal cramps, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, sore throat or hay fever-like symptoms. The Missouri Department of Natural Resources and the Tulsa Metropolitan Utility Authority are trying to stay ahead of this threat so that if there is a harmful algal bloom threatening drinking water supplies, they will know how to combat it.

That’s where Shi and her research team come in. They have been collecting water from the different treatment facilities, bringing the water samples to Shi’s lab, and spiking the water with different types of toxic algae they cultured in their lab.

“The real problem is the toxin, but the toxin comes from the harmful algae,” Shi says. “So, how do we kill the algae, control the bloom, while at the same time not let the toxins leach out? There are a lot of factors and a lot of different experiments to perform.”

For now, Shi is happy that her research is valuable to her students and the public.

“These students are solving real-world problems to help the people of Missouri, the United States and the world,” she says.

Her research is supported by funding from the Missouri River Water Supplies Association, the Missouri Department of Natural Resources and the Tulsa Metropolitan Utility Authority.