Groundwater mapping, managed flooding may help stop sinking

Posted by magazine

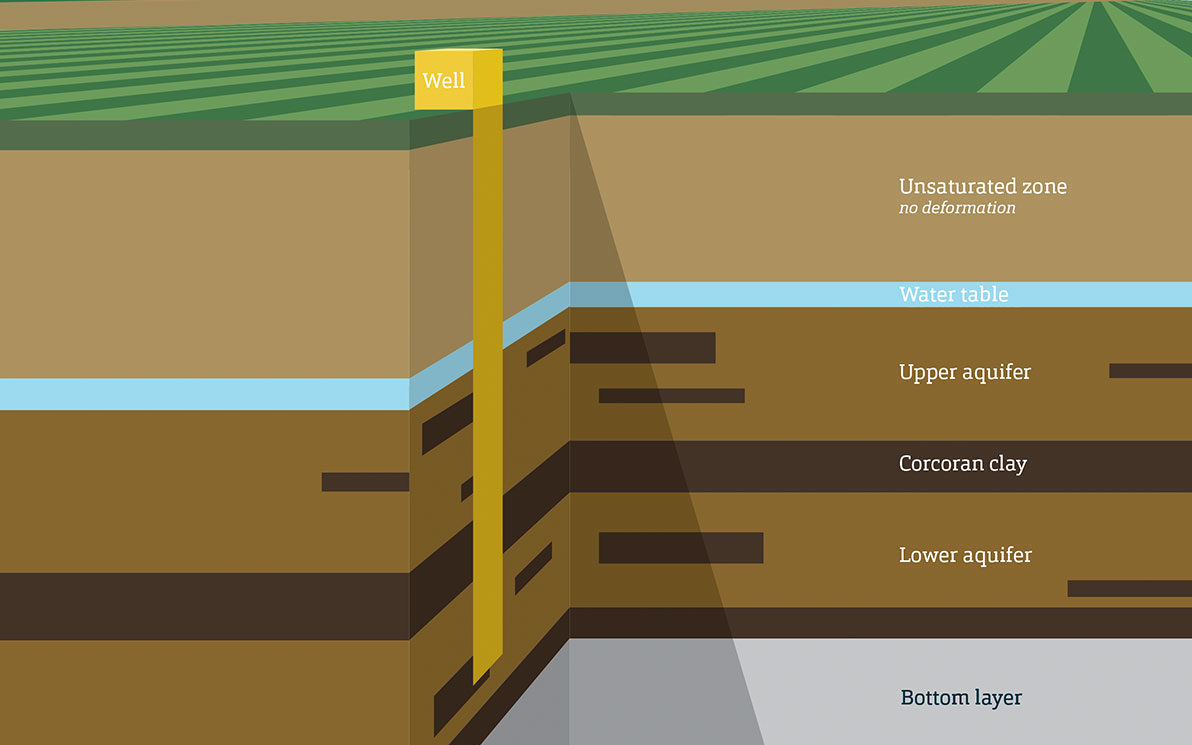

Conceptual model showing the subsurface hydrostratigraphy of the study area, represented by a five-layer model.

Parts of California’s Central Valley, the state’s most productive farm region, sunk as much as 28 feet during the first half of the 20th century, and if modeling is accurate, the ground will sink another 13 feet or more over the next 20 years.

Ryan Smith, an assistant professor of geological engineering at S&T, working with colleagues at Stanford University, developed the model. It could help water managers map precisely where groundwater recharge is most needed to replenish aquifers in the area.

The research, which was published in the journal Water Resources Research, suggests managed flooding of the ground above the aquifers.

Smith says the amount of water exiting the Central Valley’s aquifers far surpasses the amount of water trickling back in. That overdraft has caused land across much of the region to sink, permanently depleting groundwater storage capacity and damaging infrastructure.

Knowing where water will go underground depends on mapping the intricate channels of sand and gravel that interlace tightly packed clays and silts. In California, that information often comes from drilling contractors’ reports to state regulators, which are expensive to acquire and do not cover areas between or beneath the drilled wells. As a result, the most common approach to dealing with subsidence, the downward settling or sinking of the ground’s surface, is reactive, Smith says.

“If we are proactively managing, then we can prevent unrecoverable storage loss,” says Smith.