Google electromagnetic interference

Posted by magazine

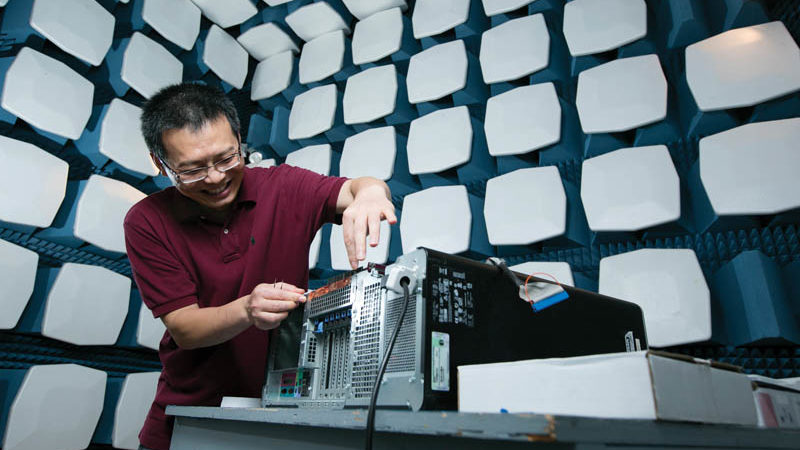

Dr. Jun Fan in the semi-anechoic chamber at the Electromagnetic Compatibility Laboratory at Hy-Point. Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

A decade from now, your smartphone won’t look anything like it does today — at least on the inside.

With 5G technology, the devices will also be 10 times faster than they are today. And self‑driving cars won’t be a novelty, they will be part of your daily commute.

Jun Fan, a professor of electrical and computer engineering and a researcher in S&T’s Electromagnetic Compatibility Lab, is using a grant from Google to meet those goals — and do it safely — by deciphering and solving the problems of electromagnetic interference inherent in the systems.

Every electronic device emits electromagnetic radiation, and cellphones are no different with their multiple channels and multiple digital and analog circuits. “Noise,” or electromagnetic interference, affects the performance of multiple input, multiple output (MIMO) systems by slowing the speed of apps and downloads, dropping calls and making calls you do receive sometimes hard to hear clearly.

Those issues can be frustrating, but they’re not life-threatening. But keeping self‑driving cars safe is.

“We need to make these devices, phones and cars, work in a real-world setting,” Fan says.

His lab is a fully enclosed electromagnetic quiet room equipped with wave-absorbing material on three walls and the ceiling, with big pads and smaller egg crate shapes. Here the researchers gauge the radiation from electronic devices’ transmitters and receivers.

The information gleaned there can be applicable to autonomous automobiles, Fan says. Just as reducing interference in phones can lead to better performance, reducing interference in and among self-driving cars will make them safer when multiple vehicles are on the road. Of course, infrastructure investment in and surrounding roads will be necessary to keep the communications between autos clear and direct.