Fueling space flight

Posted by magazine

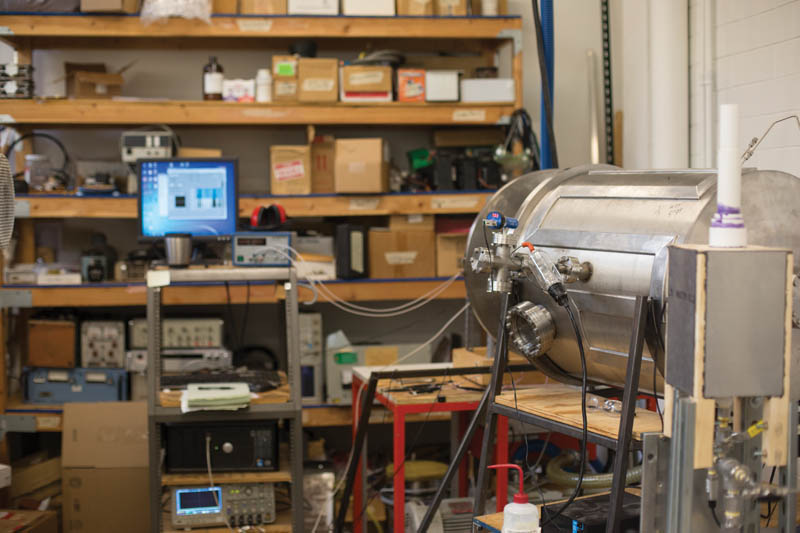

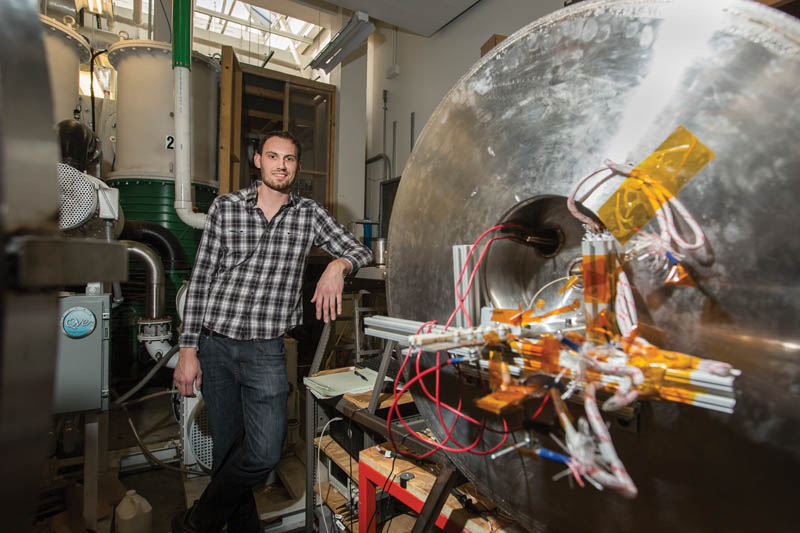

Steve Berg Sam O’Keefe/Missouri S&T

It started with a boyhood dream of becoming an astronaut fueled from watching the 1995 Hollywood portrayal of the ill‑fated Apollo 13 lunar mission.

It ended — or rather, took a detour — after a teenage growth spurt propelled Steven Berg beyond NASA’s 6-foot-4 height limit for space travelers. The federal agency’s loss is Missouri S&T’s gain, as Berg’s fascination with space led to a postdoctoral fellowship in the Aerospace Plasma Laboratory under the supervision of associate professor Josh Rovey, his thesis advisor.

After nearly a decade in the department, Berg, AE’10, MS AE’12, PhD AE’15, joined SpaceX in 2015 as a propulsion engineer and test engineer working on the Falcon 9 rocket’s second stage in Texas and southern California.

The SpaceX gig was heavy stuff for a 20-something engineer, admits Berg, who spent two years as a hurdler and high jumper for the S&T track team. But just months into the new job, when Rovey offered his former pupil the chance to return to Rolla as a postdoc to continue research into multi-mode micropropulsion — and hopefully spin off those efforts into a commercial venture — he didn’t hesitate to trade lunches at Manhattan Beach for a windowless office in the basement of Toomey Hall.

“This may be my only chance to do this,” he says.

With the help of several graduate student researchers, Berg is seeking to advance spacecraft propulsion by combining its two traditional systems, chemical and electric, into one that can tap into either, depending upon circumstances.

“Traditionally, propulsion systems have been either one of those separately, but not both. Our propulsion system does both in a single package: one propellant, one tank, one feed line and one thruster.”

The advantage of such a system? Its ability to change course on the fly and react to unforeseen circumstances, from shifting weather patterns to unexpected military maneuvers.

“Our system would save a huge amount of time and money in development costs, since you have the flexibility to significantly change the flight profile as needs arise, or requirements change, without adjusting the propulsion system hardware,” Berg says. “You wouldn’t have to retest all the components you design, or redesign all the components you already tested.”