The air up there

Posted by Mary Helen Stoltz

Before the era of jet planes, scientists didn’t realize that thunderstorm cells could stretch as high as 90,000 feet into the atmosphere.

“No one had flown high enough to see they could reach that altitude,” says Lee M. Etnyre, Phys’60.

In those days, to study the wind shear in Earth’s upper atmosphere, the U.S. Navy would launch a rocket from an airplane that released an instrument data recording package at high altitude, and then watch it descend. A large radar antenna on top of the plane would track the descending package to help measure wind shear and speed at high altitude. “It was an early way to measure the jet stream,” Etnyre says.

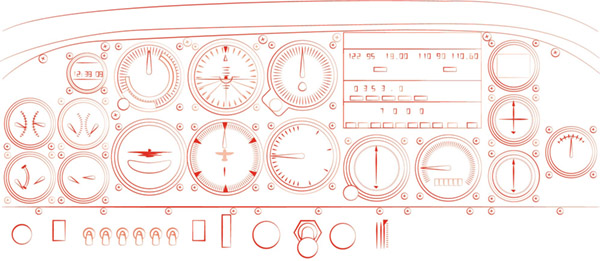

While working for the U.S. Naval Air Development Center in the early 1960s, Etnyre patented this system, which takes that analog aircraft navigation data and converts it to a digital representation of the plane’s position compared to a fixed location on the ground.

“I learned how to use existing devices and technology, originally designed with other applications in mind, and integrate them into a unique combination to solve a new technical problem,” Etnyre says.

Etnyre also holds a patent for a satellite navigation system that improves an aircraft’s ability to land safely when adverse weather conditions limit visibility, and another to suppress duplication of aircraft surveillance images on a cockpit display of nearby air traffic currently used in all of Garmin’s cockpit displays of air traffic.