A front-row seat to the history of space exploration

Posted by Mary Helen Stoltz

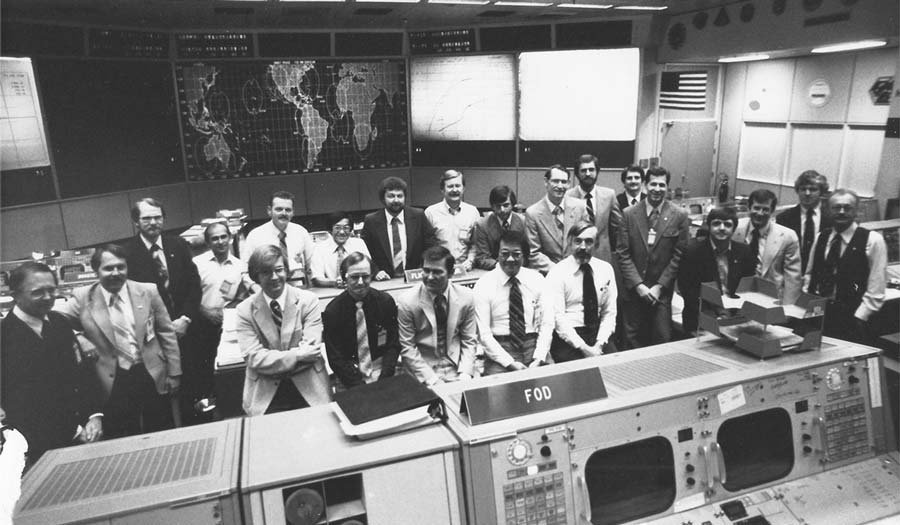

Ron Epps, in the center of the back row, pictured in 1981 with the STS-1 Flight Control Team in Johnson Space Center’s Mission Control. STS-1 was the first orbital flight of NASA’s Space Shuttle Program. Photo submitted by Ron Epps, Phys’67.

In 1963, Ron Epps, Phys’67, rode his 1951 Harley Davidson Panhead from Mount Vernon, Mo., to Rolla to attend the Missouri School of Mines on a Carnation Milk scholarship. When he crossed the stage as a first-generation graduate, NASA was preparing to send a man to the moon.

Epps had 17 job offers at graduation, but NASA’s offer caught his attention.

“NASA recruited me heavily,” Epps says. “I actually got a Western Union telegram that said, ‘We think you could help this country land a man on the moon and we’d like you to come to work for us.’”

Epps reported to the Manned Spacecraft Center (later named the Johnson Space Center) in Houston on June 5, 1967 — a week after graduation. He served his entire career there, taking part in some of the space program’s most significant events.

“I have been extremely fortunate to be one of those who participated in the development of the U.S. space exploration program,” Epps says. His 38-year career spanned the Apollo, Skylab, Apollo-Soyuz, space shuttle and International Space Station programs. “It has been a great ride, and it all started with a degree in physics from Rolla.”

Epps started work as an aerospace technologist with the Landing and Recovery Division, serving as a technical advisor to the U.S. Navy. Assigned to recovery ships for Apollo 8, 9 and 14, he was deployed all over the world to recover spacecraft returning from the moon and to cover deep space aborts — unplanned landings following system failures.

“It has been a great ride, and it all started with a degree in physics from Rolla.”

Ron Epps, Phys’67

“I was making friends with flight controllers in Mission Control, learning lunar trajectories and orbital mechanics — it fit my degree quite well.

“The Apollo program was truly a technical marvel,” Epps says. “I don’t think any group of talented individuals has ever done so much for the country outside of wartime. At the time, I thought space flights to the moon and beyond would go on forever, but budget cuts brought an end to the Apollo program.”

After Apollo 14, Epps spent the next 12 years as a flight dynamics officer in Mission Control, responsible for all aspects of trajectory operations.

“After liftoff, you monitor the vehicle’s performance and flight path and call abort modes if required. Your main job is to watch the vehicle’s flight path uphill and determine how much energy it’s got and how much it needs to get to orbit.”

“I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind or more important in the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish.”

President John F. Kennedy in a May 1961 special address to a joint session of Congress

Epps manned a console on the front row of the Mission Control Center, an area known as “the Trench,” during the two final Apollo flights, the launch of Skylab, the docking of the Apollo spacecraft with the Russian Soyuz capsule, and the first nine space shuttle flights.

The Apollo-Soyuz program ended in 1975 and Epps turned 30 at the console. From there, he began prepping for the shuttle era.

He started by writing the requirements to get the Apollo software to work on the space shuttle missions. Some of the basic orbit and rendezvous software could be easily transitioned, he says, but the real problem was developing code to get the shuttle off the ground and into orbit and determining abort modes.

“It was a totally different beast,” Epps says of the space shuttle. “Apollo was a ballistic vehicle. The shuttle, though, was designed to be a partially reusable winged vehicle with solid rockets and

an external tank.”

After weeks of deliberation and discussion, the solution came to Epps at 4:30 a.m. He woke his wife shouting “I figured it out!” as he ran down the hall.

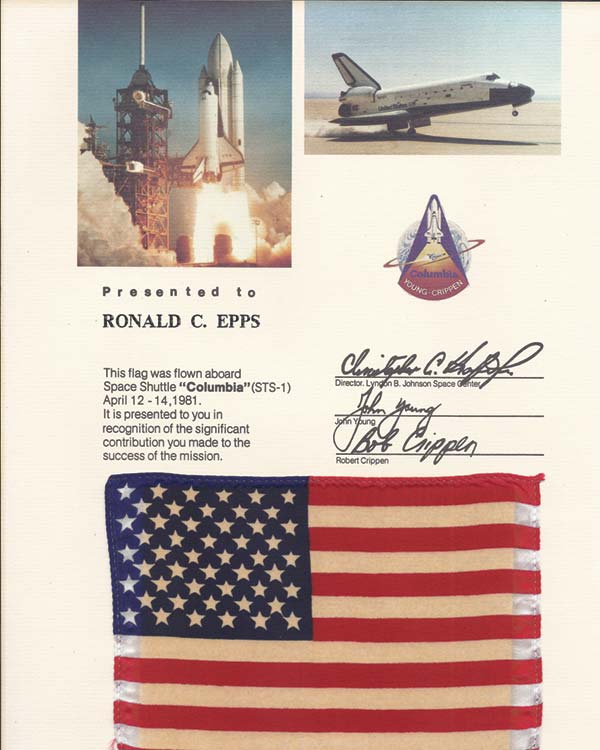

Epps’ solution, the Abort Region Determinator (ARD), was used to monitor the shuttle’s ascent trajectory and to determine abort modes for the entire shuttle program. Epps tested the system for two years in 1,080 integrated ascent simulations with the STS-1 crew. “Utilizing the ARD as a member of the hand-picked STS-1 flight control team was a magnificent achievement,” he says.

After the first nine shuttle missions, Epps spent 36 months training astronauts for shuttle ascent and entry. In 1986, he became chief project engineer for all projects supporting Mission Control

operations and shuttle space flight simulators. After the Challenger accident, Epps was awarded the NASA Exceptional Service Medal for technical management in preparation of those facilities for the shuttle’s return to spaceflight.

Epps retired in January 2005 after his wife, Peggy, was diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease. He had just completed a nine-year run as chief of the flight design and dynamics division responsible for all aspects of trajectory analysis, design and flight control operations supporting the U.S. space shuttle and space station programs. He oversaw 35 space shuttle flights, including 16 shuttle missions to the International Space Station, six shuttle-Mir missions, three Hubble Space Telescope servicing missions, 10 ISS expeditions and 25 visiting-vehicle missions to ISS.

At the close of his retirement celebration, NASA awarded Epps the agency’s highest award, the Distinguished Service Medal, for his outstanding technical contributions and exceptional leadership to the nation’s space program.

“I can’t imagine another job where the highs were so high and the lows were so low,” Epps says. “It was a great ride for a boy from Mount Vernon.”