Snakeasaurus: S&T grad makes a BIG discovery

Posted by

As miners dig deeper and deeper into an open coal pit in Colombia, millions of years of history are displaced. On a fossil-hunting expedition to one of these pits in 2006, Carlos Jaramillo’s team found some big bones that belonged to a super-sized creature.

Sixty million years ago, not long after the dinosaurs died out, the tropics were warmer than they are today. And the creatures, though not dinosaurs, were bigger. Jaramillo, MS GGph’95, a scientist at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama, figured the vertebrae he found belonged to a massive crocodile.

(illustration by Jason Bourque, University of Florida)

“Two years later, a student compared the vertebrae to the skeleton of a modern anaconda,” says Jaramillo. “Then we thought, ‘ah, yes, we have a big snake!’”

This constrictor, now considered to be the largest snake to have ever slithered the Earth, would have made a modern day anaconda look like a glorified earthworm. Jaramillo says his team actually ended up finding the fossils of 28 different snakes, ranging in size from 40 to 50 feet long with a weight in the neighborhood of 2,500-pounds.

Jaramillo and co-researchers named the constrictor Titanoboa. They published their findings in the journal Nature in February 2009.

Carlos Jaramillo, MS GGph’95, found the fossils of Titanoboa in an open coal pit in Colombia.

In addition to being the biggest snake, Titanoboa is the largest non-marine vertebrate ever discovered. It fed on crocodiles and giant turtles by squeezing them to death and swallowing them whole. Previously, the largest known snake was Gigantophis, which was at least 33 feet long and lived in Egypt about 39 million years ago. Today, the longest snake is the reticulated python, which grows up to 32 feet. The anaconda is bulkier, but maxes out at 25 feet.

Open coal pits like the one in Colombia are excellent places to find evidence from the past because they preserve organic matter well. Jaramillo has found pollen, flowers, seeds, fruits, crocodiles, turtles, lizards, fresh water barracudas, crabs, bivalves, gastropods, echinoids, brachiopods, you name it. One common denominator among a lot of the bones and fossils dating back to approximately 60 million years ago is their size. The generous proportions can be attributed to climate.

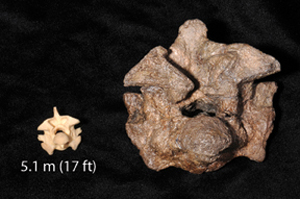

The hefty vertebrae of Titanoboa (right) dwarfs that of a modern anaconda. (photo by Jason Head and John Bloch, University of Florida)

Cold-blooded animals that depend on size to maintain metabolism grow bigger in warmer environments. According to Jaramillo, plants and animals like Titanoboa were living at temperatures that were 7 to 10 degrees higher than they are now. Carbon dioxide levels were also found to be elevated. That means tropical rainforests had the potential to thrive during past periods of global warming.

Jaramillo’s scientific studies have taken him to Panama, Brazil, Peru, Ecuador, Venezuela, Costa Rica and Nigeria; and he goes back to Colombia often. In his line of work, Jaramillo says he sees plenty of snakes that are still very much alive: “Big ones, small ones, ones with poison, without poison … it’s a common animal we find in the field. You have to learn to live with them.”

But, fortunately, none of us has to learn to live with a snake as large as Titanoboa.

“Oh, I wouldn’t want to meet up with Titanoboa,” Jaramillo says quickly, thinking about the consequences of such an encounter. “My God!”