re:newable vehicles

Posted by Mindy Limback

A plug-in hybrid fleet that’s powered purely off renewable energy results means we’ll have emission-free energy that can be dispatched at the request of power grid operators. Illustration by Jeff Harper.

Two energy researchers at Missouri S&T are revved up about the future of plug-in hybrid vehicles, what they see as the next generation of electrically driven automobiles.

“I would compare my excitement about plug-in hybrid technology to where we were with the Internet in the 1980s,” says Mariesa Crow, the Fred W. Finley Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and director of the Energy Research and Development Center. “The utility industry should be going gung-ho about plug-in hybrids.”

Crow and Mehdi Ferdowsi, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering at Missouri S&T, are joined by automakers, businesses and politicians alike in a desire to accelerate the development of plug-in technology. Even Internet giant Google has joined the mix, with its philanthropic arm planning to invest $11 million in the initiative.

Although plug-in hybrids aren’t currently in production, existing hybrid vehicles, such as the Toyota Prius, can be modified into a “plug-in” hybrid for a few thousand dollars. The modification, which allows the vehicle to be plugged into a regular electrical outlet to recharge, includes adding batteries and an onboard AC-to-DC charger. Unlike all-electric vehicles, hybrid vehicles are powered by both a traditional internal combustion engine and batteries.

Hybrid vehicles get better fuel economy than their solely gas-powered cousins and don’t face driving range restrictions, like the EV1, an all-electric vehicle developed by GM in the late 1990s. In the future Ferdowsi and Crow envision, at least 10 percent of the vehicles on the road in the year 2020 will be in the form of a hybrid car that has an onboard energy storage unit. While the owner is at work, the vehicle would be plugged into the power grid, and its storage units would be used for grid regulation and peak-load shaving, a technique that helps stabilize energy prices.

“While the vehicle is plugged in, the state of the charge of the onboard energy storage unit would be optimized based on several factors, such as the driver’s previous driving patterns and the forecasted daily power demand of the grid,” Ferdowsi explains.

When the owner returns home, the vehicle would be plugged into a regular electrical outlet to recharge. A 2006 California study found that the cost to plug in the vehicle overnight would have been equivalent to less than 80 cents a gallon, at a time when gasoline was selling for more than $3 a gallon.

“It has been proven that employing energy storage systems improves the efficiency and reliability of the electric power generation as well as the power train of the vehicles,” Ferdowsi explains. “If both the transportation and electric power generation sectors used the same energy storage systems, we could integrate the two and improve the efficiency, fuel economy and reliability of both systems.”

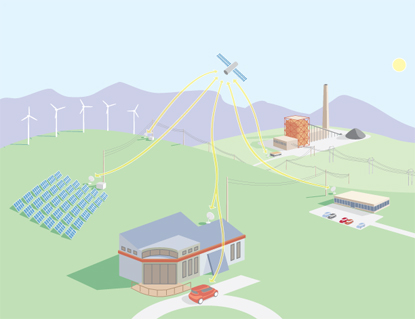

In Kansas City, Mo., officials plan to purchase a fleet of plug-in hybrid vehicles to use downtown for city business. Power for the vehicles may also come from renewable sources, such as wind and solar energy. Illustration by Jeff Harper.

That’s the concept behind the $1.7 million demonstration project involving Kokam America Inc., the city of Kansas City, Mo., and the Missouri Transportation Institute. Funding for the project was secured by Sen. Kit Bond in the omnibus appropriations bill, which was signed by President George W. Bush in late December.

“We are currently partnering with the city of Kansas City in demonstrating the viability of electric and plug-in electric vehicles within the city’s vehicle fleet,” says Don Nissanka, president of Kokam America. “The project will include the use of alternative energy sources for recharging the lithium batteries that will be utilized by the fleet vehicles and the ability to return energy to the city’s power grid.”

Kansas City plans to purchase roughly a dozen small to mid-size plug-in hybrid sedans for employees to drive while they serve community needs. The vehicles, using Kokam batteries, would be used in downtown Kansas City. “We think it’s a good way to address self-sustaining transportation in urban areas,” says Robert Rives, manager of facilities management for Kansas City.

Crow and Ferdowsi say it’s important to note that although plug-in hybrids are low emission, they aren’t emission free. The group wants to reduce emissions even further by introducing renewable energy, such as wind and solar power, into the equation and creating a zero carbon footprint for drivers.

“The concept of zero emissions is one of the main aspects that sets our project apart from others,” says Rives. “Our goal is to charge the vehicles through renewable resources.”

Renewable sources of energy, such as wind and solar, generate electric power that can be delivered to the power grid. Plug-in hybrid vehicles can then use that power once they are connected to the grid.

“The power grid will be like an interface between renewables and plug-in hybrids,” Ferdowsi explains. “In an ideal case, you can always sell energy back to utility companies; however, it depends on the regulations of the particular state.”

The future envisioned by Missouri S&T researchers includes millions of hybrid electric vehicles plugged in to the power grid. Each vehicle would have an onboard, embedded system that intelligently manages power generation and would interact wirelessly with energy management centers. The efficiency, fuel economy and reliability of both the transportation and electric power generation sectors would be improved because of this integration.

The carbon footprint of plug-in hybrids will be lowered once renewable energy sources are incorporated, which will also reduce their contribution to global warming.

“A plug-in hybrid fleet that’s powered purely off renewable energy results means we’ll have emission-free energy that can be dispatched at the request of power grid operators,” Crow says. “This will happen, and it will start in forward-thinking cities like Kansas City.”