re:growing bones

Posted by

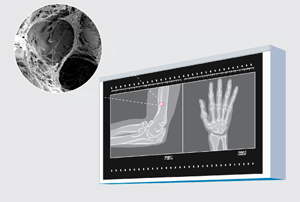

Human bone cells are attracted to porous medical scaffolding made out of bioactive glasses. Illustration by Jeff Harper.

Delbert Day, CerE’58, MS CerE’60, says it’s like seeding a fishing environment by throwing an old Christmas tree into the water. The submerged tree provides good pockets of cover for all kinds of fish. But this isn’t really a discussion about aquatic habitats. Day is trying to explain why human bone cells would want to colonize medical scaffolding made out of glass fibers.

“Nature abhors a void,” he says. “And the body likes certain kinds of glass.”

A Curators’ Professor emeritus of ceramic engineering, Day has developed a number of new applications for glass, including the treatment of liver cancer with tiny, radioactive glass spheres. In 1985, he co-founded Mo-Sci Corp., a world leader in glass precision technology. Currently, Day and a group of Missouri S&T researchers are developing 3-D scaffolds made out of bioactive glasses. And, yes, they plan to use the scaffolds for bone regeneration.

“Cells can get inside the scaffolding, grow, and develop in the pores,” Day says, “just like the fish colonize the Christmas tree.”

But here’s where the analogy departs. Unlike the tree, which never becomes one with the fish, the scaffolding eventually does become part of the bone.

Right now, titanium rods are often used to repair badly damaged bones. But Day and his colleagues say the glass scaffolding is, mechanically, much closer to the composition of real bone. Compared to metal implants, which are smooth and rigid, the scaffolding is porous and downright hospitable.

“Over time, the scaffolding would become indistinguishable from bone,” says Roger Brown, a professor of biological sciences who is working on the project. “It becomes part of the bone structure.”

The Missouri S&T researchers have formed a partnership – officially called the Consortium for Bone and Tissue Repair and Regeneration – with researchers at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. “We do

the materials work here,” explains Len Rahaman, a professor of materials science and engineering at Missouri S&T who is working with Day and Brown. “They do the clinical work at UMKC.”

Four bioactive glasses selected by the Missouri S&T researchers are being evaluated in Kansas City. Once the best glasses are identified, Rahaman will lead the effort to build new scaffolds in Rolla. Prototypes will then be placed in animals, and, if everything goes according to plan, the method will ultimately be tested in humans.

In addition to mending arm and leg bones, the glass scaffolding could be used to repair damaged joints and make some dental surgeries more efficient.

If the scaffolding works like they think it will, the Missouri S&T team will have played a big role in changing the way medical professionals treat bone trauma (just as Day was a pioneer in finding a new way to treat liver cancer). But Day, Brown and Rahaman don’t want to stop there. They hope to develop something that really speeds up the process of regeneration – something even better that could be quickly employed in emergency rooms and on the battlefield.

“Bone regeneration takes a number of weeks,” says Brown, not satisfied with how far the cutting-edge research has already come. “We eventually need something we can implant that provides load-bearing strength much faster.”

Wayne Huebner, CerE’82, PhD CerE’87, chair of the materials science and engineering department, envisions a future where information on human bones is catalogued like fingerprints are today. “In the future, humans may have a computer-aided design file of their entire skeleton made by magnetic resonance imaging,” Huebner says. “Then, if someone needed a new bone, a rapid-prototyping machine could make one out of the bioactive glass.

“A surgeon would simply install it and your body would do the rest, converting the glass into an entirely new bone.”