Farming new fuels

Posted by Mindy Limback

Cattle and corn may soon connect at the gas pump

Ethanol pulled into the fast lane in Missouri this year when Gov. Matt Blunt approved a bill requiring that gasoline sold in the state be blended with at least 10 percent of the corn-based biofuel by Jan. 1, 2008.

As with most alternative sources of energy, ethanol has significant benefits: it‘s a clean-burning, high-octane fuel that can help keep gas prices down by increasing and diversifying the nation‘s fuel supply. Yet there‘s a major catch: energy is needed to grow corn and turn it into ethanol.

In ethanol production, the starch portion of the corn is fermented into alcohol and then distilled. Natural gas and electricity are used to run the ethanol plant, powering everything from the hammer mill that grinds the feedstock into a fine powder to the boilers that liquefy the starches.

This dependence on fossil fuels to manufacture ethanol dampens its future as an alternative source of energy, says Joel Burken, associate professor of civil, architectural and environmental engineering.

This dependence on fossil fuels to manufacture ethanol dampens its future as an alternative source of energy, says Joel Burken, associate professor of civil, architectural and environmental engineering.

Burken and his colleagues in the UMR Environmental Research Center (ERC) are working with the agricultural industry to brighten that outlook by replacing a portion of the fossil fuels used in ethanol production with biogas, which comes from cattle manure and waste. If the team is successful, cattle and corn farms may soon be housed together with ethanol production and waste management to create a self-sustaining, “closed-loop” agricultural park.

“Arguably the most important issue facing the United States and the world is how do we develop a sustainable economy – that is, an economy that is not simply based on rapid depletion of resources,” says ERC director Craig Adams, the John and Susan Mathes Missouri Chair of Environmental Engineering in the civil, architectural and environmental engineering department. “A key element of sustainability must be the development and implementation of waste-to-energy and waste-to-product technologies.”

The cow connection

Locating cattle, corn and ethanol production makes some waste-to-energy methods feasible. Ethanol plants are already being built closer to animal production facilities today because distiller’s feed – a byproduct of ethanol production – is rich in protein and can be fed to cattle. The porridge-like feed is typically dried to extend its shelf life, but drying consumes up to a fifth of the ethanol plant’s total energy output. Placing a cattle operation near the ethanol plant eliminates drying as the feed could be eaten promptly.

Cattle operations, like breweries and food processing plants, typically have a high organic waste load. Inside the anaerobic digester, tiny microbes turn waste into biogas (a mixture of methane and carbon dioxide), and methane in biogas is an energy source. In the past, the anaerobic metabolism has been used mainly to treat the waste because there wasn’t an economical method to use the biogas for energy.

In the new “agricultural industrial park” concept, cattle manure and ethanol plant waste would both be piped into an anaerobic digester, where a community of microbes breaks down the complex organic waste. One group of bacteria would consume the fermenting bacterial waste and in turn produce molecules that another group of bacteria would metabolize, giving off biogas as a by-product. The biogas would then be captured to help power the ethanol facility.

“These living organisms rely on each other to provide sources of food and maintenance of conditions such as the pH in the anaerobic digester,” explains Melanie Mormile, associate professor of biological sciences. “The proper balance of microbes is important because if there are upsets in the bacterial populations then there can be an accumulation of intermediate products and the pH can drop. This can cause digester failure. On the other hand, a balanced microbial community will actively form methane.”

Broadly, as energy prices have shot up, biogas from waste digesters or landfills has been used directly for heat or even to generate electricity. “This is really a case of one person’s waste is another person’s raw material,” Burken says. “It‘s anaerobic digestion and proximity that make it all viable.”

This waste to energy concept is used successfully at the Anheuser-Busch St. Louis Brewery, where one of the world‘s largest anaerobic systems turns wastewater into energy. The produced biogas provides 10 to 15 percent of the boiler fuel used by the brewery. “Anheuser-Busch saves millions in diversion from what they don’t pay in sewer charges and what they recoup in energy,” Burken adds.

An even more “closed-loop” system could be made possible by locating cornfields nearby. “As the anaerobic digestion takes place, a liquid waste stream is left over,” Burken adds. “The liquid, which is still high in nutrient content, can go right on the fields as a fertilizer and irrigation.”

The smell of success

Fifteen counties in Missouri have already passed health ordinances aimed at deterring livestock operations from building new facilities within their limits. For some residents, the idea of jointly locating two odor-producing operations, feedlots and ethanol plants, may not seem like a good idea, but proximity is key to making the operations economically viable.

“We want a situation where we have the right mix of using good technology and being a good neighbor,” says Dan Engemann, assistant to the director of Missouri’s Department of Agriculture. “Agriculture is our state‘s largest industry and animal agriculture is what we do best in this state. We believe it‘s not that they‘re opposed to animals, just the offensive odors that may be emitted. Odor levels can really aggravate people. The department appreciates UMR‘s assistance in letting people know that there are solutions to these issues.”

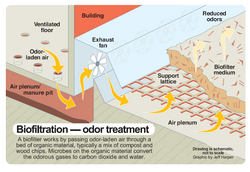

The ERC team believes that offensive odors can be neutralized using the enclosed digesters and integrating biofilters and other technologies into the new facilities. “A biofilter is a simple but highly effective technology,” explains Mark Fitch, associate professor of civil, architectural and environmental engineering at UMR. “It‘s not specialized or expensive, and simply uses the ability of microorganisms to consume the odorous compounds from the air. Adding a biofilter as a retrofit can be challenging, so having a system for odor elimination in the design is just being smart and a good neighbor.”

Unlike a dust filter that must be cleaned, a biofilter is a living ecosystem. Biofilters typically consist of a bed of sawdust or wood chips, a watering system, a fan and microbes that feed on odorous gases. The biofilters would be placed on the side of the barn and the ethanol plant.

The ERC previously demonstrated this technique for a farm by taking a truckload of compost from the composting center for Phelps County. They placed pallets on the ground with a screen and put the waste on top.

“As with most animal barns, there was an existing fan that we ducted to the biofilter,” Fitch adds. “The resulting decrease in odor was 20-200 times less than before the biofilter.”

The team is also studying whether the biofilters could be eliminated if the facilities are intimately close. The manure and biosolids from the ethanol plant could be digested to produce methane, which can be burned for energy. The air to mix with the methane then could come from the barn, carrying the odors, and the combustion process then burns the odors.

“Anytime you burn, you have to have air, so the barn would be just like your car‘s carburetor as the source of that air,” Fitch explains. “If we run ductwork from the barn, we could use the air from the barn and the burning will destroy the odor just as well as a biofilter would.”

Down on the farm

The research team is also investigating whether this idea could be used on an average, family-owned farm. As with larger operations, manure from the cattle would go directly to an anaerobic digester for methane generation. In the winter, the farm could burn it for heat in the home. Or the methane could be stored for a few days on site in a small generator and used during peak energy demand, such as during the middle of the afternoon in the summer.

“Existing power plants easily meet average electrical needs and work well when running steadily,” Burken says. “When the demand rises up above their production for short periods, these small generators could be remotely flipped on and help supply the grid during these peak need periods.”

Tim Echelmeier of Echo-L Holstein in central Missouri sees several benefits to adding an anaerobic digester to his fourth-generation, family-owned farm, and has received a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to explore the idea.

If implemented, the on-site anaerobic digester would convert the manure from his 1,100 head of cattle into biogas and a liquid fertilizer.

“We believe we could generate approximately 10 to 20 percent more energy than the farm would use itself,” says Echelmeier, who returned to the family farm after earning a master’s degree in business administration from William Woods University. “In addition, the organic fertilizer has lots of intrinsic value because it would cut down on chemicals we need to spray and it’s more stable and readily usable by plants.

“All farmers rely on the land for a living. As livestock operations continue to grow, farmers are trying to work in the most ecological way to utilize everything that comes out of that farm. We need to make it worth the farmer’s investment.”